Today I'm

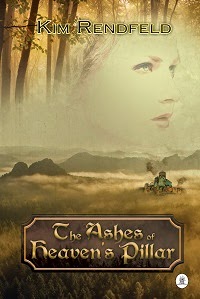

delighted to welcome Kim Rendfeld to "Fall in Love with History". Kim

writes historical fiction and is celebrating a new release "The Ashes of

Heaven's Pillar", which I have added to my TBR pile! Today, Kim posts on

"The Medieval Midwife’s Unique Place in Society", so without further

ado I'll hand over to Kim

G x

The Medieval Midwife’s Unique Place in Society

By Kim

Rendfeld

The

medieval midwife faced a lot of pressure. Not only was she to do her best to

help mother and baby survive the birth. As the only layperson with the

authority to baptize, she was responsible for the newborn’s soul.

In the

Middle Ages, childbirth must have been greeted with a mix of emotions. A family

might look forward to the arrival of an heir, but the process was so risky that

women were urged to confess their sins before they went into labor.

Whether

the delivery was in a low-ceilinged lying-in chamber of a noble house or a

one-room peasant’s hut, the last person an expectant mother wanted was her

husband or a doctor. Medieval folk considered childbirth part of life, not

medicine. Better for the men to be praying at church and let the midwife take

charge of the situation.

A midwife learned

her craft from her own mother. Her tools might include a birthing stool, a

sharp knife, ointments, herbs, the right foot of a crane, a piece of jasper,

spells in case the labor was particularly difficult, a basin to bathe the baby,

honey, and salt. The Church did not condemn the midwife for touching another

woman in an intimate area, since her duties required it.

Officially,

the clergy frowned on spells and charms, but as they did with most other white

magic, they ignored it for the most part. Medieval folk in general saw magic as

a tool, one that could be used for good or evil. After all, the laity often wore amulets

alongside their crosses. Clerics were much more concerned if the midwife said

the wrong words while baptizing a child in danger of dying before a priest

could perform the rite.

Inside the

birthing chamber, the midwife had her own assistants, and a few of the mother’s

friends and relatives attended to offer encouragement. Doors and cupboard

drawers were open; knots were untied. Even the mother’s hair might be loosened

and free of pins.

The

midwife would do what she could to hasten labor, such as rubbing an ointment on

the mother’s belly or giving her a potion with ergot. When the time came, the

mother would sit on the birthing stool to deliver the child. Midwives knew to

wash and oil their hands before they brought the child into the world. The only

time a midwife would perform a Caesarean, without anesthesia, was when the

mother was dying or already dead.

The

midwife was the one to cut the umbilical cord four finger lengths, wash the

baby, and use honey on the child’s gums and palette to stimulate appetite. After

the infant was wrapped in swaddling, the midwife would present the child to the

father.

In noble

houses, the mother would remain confined to the lying-in chamber for a month,

and only the midwife, servants, and the mother’s close friends were allowed to visit

during her recovery.

I needed

to research medieval childbirth for two scenes in my latest release, The Ashes of Heaven’s Pillar. One goes

reasonably well; the other goes very, very wrong. In this scene, Sunwynn, the

daughter of my heroine, Leova, is the maid to the expectant mother. Both

Sunwynn’s and Leova’s well-being depend on the well-being of Countess Gerhilda.

|

| Click for a link |

Excerpt:

When

Gerhilda screamed and doubled over, the midwife rushed to her. The old woman

lifted Gerhilda’s skirts and felt her belly. “The child is coming,” she called.

“Get her to the birthing stool.”

The

midwife washed and oiled her hands and sat on a stool in front of Gerhilda,

whose skirts were hiked to her waist.

“I’m here,

my lady. Behind you,” Sunwynn whispered.

At

Sunwynn’s elbow, one of the midwife’s assistants held a cup smelling of strong

wine.

“Ergot?”

the midwife asked her assistant. “Good. My lady, drink the potion. It will

hasten the birth and might stop the bleeding.”

As

Gerhilda downed the wine, Sunwynn prayed, Mother

of God, let this work.

The

midwife reached for Gerhilda. The grim lines in her face deepened.

“Afterbirth’s first.”

The room

was silent except for Gerhilda’s grunts. Sunwynn’s limbs grew rigid. She felt

her mother’s hand on her shoulder.

“I have

the child,” the midwife said. When she leaned back, blood covered her arms and

chest. She cradled a listless newborn and the afterbirth.

“Another

son,” the midwife said in a monotone.

“Good,”

Gerhilda whispered.

The babe is not crying! Sunwynn stared at the infant. He was

quiet when the midwife wiped his nose and mouth. A slap to the bottom was met

with barely a whimper. Sunwynn winced. A few other women groaned.

“Daughter,

hold the jasper amulet to the countess’s belly until it’s warm,” the midwife

told an assistant.

The

midwife cut the cord and placed the child in the basin she used to wash her

hands. Three times, she used her cupped hand to pour water on the child’s head

and muttered a Latin prayer. Sunwynn shuddered. There was only one reason a

midwife would baptize a newborn.

Sunwynn

beheld her lady’s face. It was paler than anything she had ever seen.

“Pray for

me; pray for my son,” Gerhilda mumbled. Her eyes rolled, and she swooned,

slumping forward.

“Gerhilda!”

Sunwynn shrieked, shaking her lady’s shoulders. “Gerhilda! No! Come back! Come

back and live!” Sunwynn, her tears unchecked, looked at the midwife.

Sources:

Daily Life in Medieval Times by Frances and Joseph Gies

Europe after Rome: A New Cultural

History 500-1000 by

Julia M.H. Smith

“Capturing

the Wandering Womb” by Kate Phillips, The

Haverford Journal, April 2007

|

| Author: Kim Rendfeld |

Kim

Rendfeld is the author of The Cross and

the Dragon (2012, Fireship Press) and The

Ashes of Heaven’s Pillar (August 28, 2014, Fireship Press). To read the

first chapters of either novel or learn more about Kim, visit kimrendfeld.com. You’re also welcome to visit

her blog Outtakes of a Historical

Novelist at kimrendfeld.wordpress.com,

like her on Facebook at facebook.com/authorkimrendfeld,

or follow her on Twitter at @kimrendfeld, or contact her at kim [at]

kimrendfeld [dot] com.

Thanks for a great post! Very helpful for my current WIP, about a medieval midwife!

ReplyDeleteWhat a tragic scene, Kim. Seems like all the research paid off!

ReplyDelete