History is full of unsavoury details

which are unpalatable to modern tastes. Recently I’ve been researching cats in

history, and repeatedly bumped up against a particularly unpleasant truth. As

an obsessive cat lover myself, I’ve debated whether or not to post on this topic.

But my deliberations led me to decide

that writing this post might stir debate about why it’s acceptable for certain

animals to yield up their skin for human use, but not others. Or indeed, to

consider the wider debate about why it’s OK to eat some animals but not others…so

here goes…

|

| Queen Elizabeth II in her ceremonial robes featuring finest Canadian ermine |

The medieval world was very different to ours. Everything had a value,

and cats were no exception. They earnt their keep as mousers, and occasionally

got their paws under the table as pets. However, few things went to waste in

medieval times, and for those unfortunate cats who weren’t prized as hunters or

pets, they could sacrifice their skin to keep someone from a lowly caste warm.

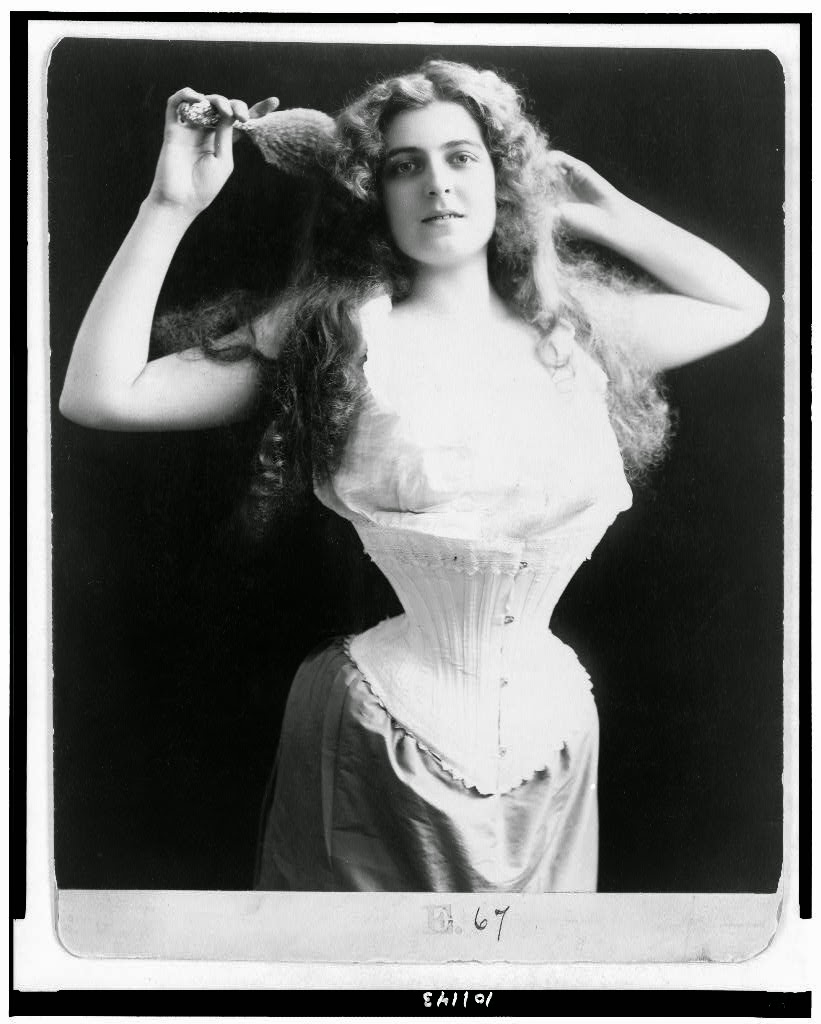

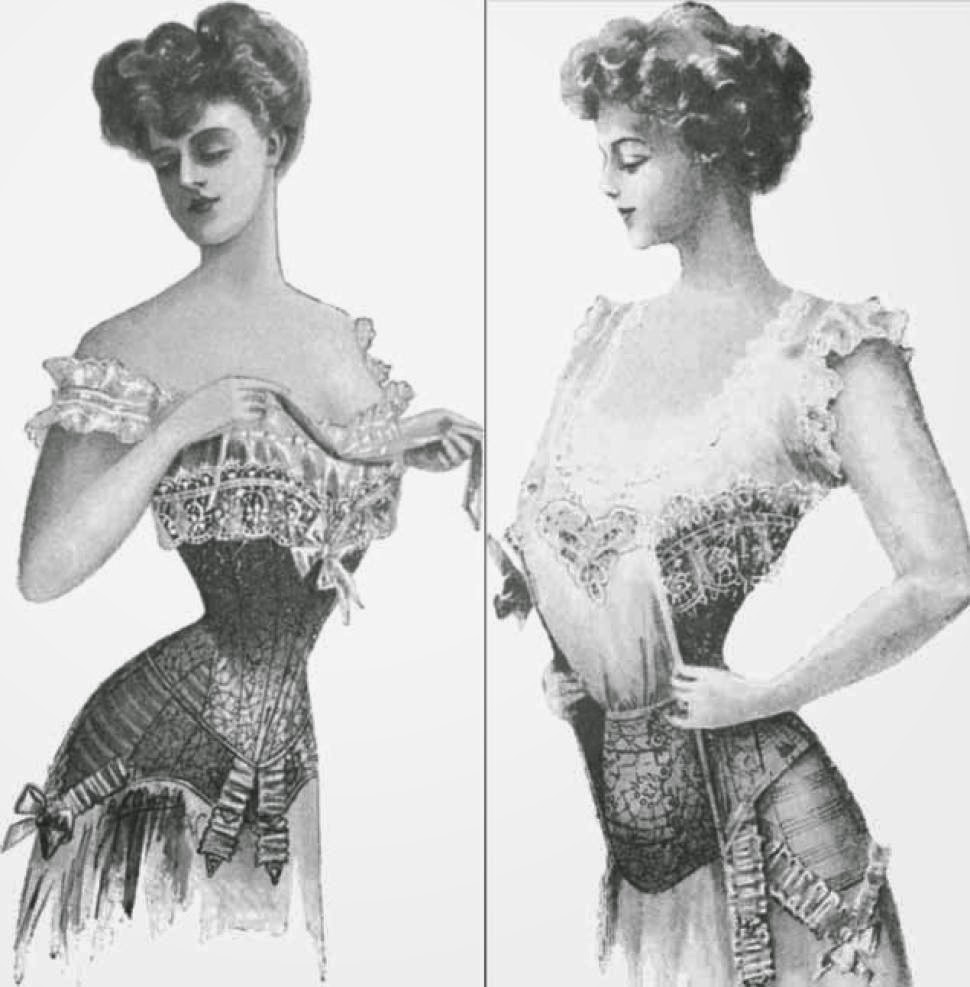

The wearing of fur was an important way to keep warm, and the type of

fur worn advertised your wealth. This wasn’t just about the purchase price of

the fur, but about making sure people didn’t ape those above them in the social

rankings. For example, sumptuary laws dictated that people under the rank of

knight were only permitted to wear certain “lowly” furs, which include lamb,

rabbit, fox…and cat.

|

| An ermine - the preserve of Royalty, unlike the humble cat |

Indeed, the only type of fur nuns were permitted to wear was catskin or lambskin, whilst monks were

permitted to trim their hoods with the pelts from cats, squirrels, lamb, or rabbit,

which were all considered lowly animals and a way of reminding the monk they

had renounced worldly goods.

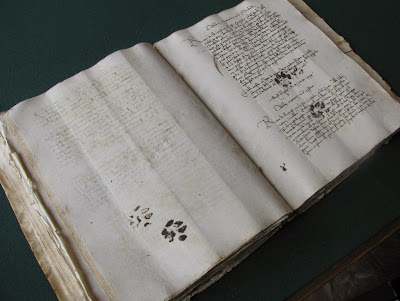

The killing of cats for their skins was widespread and taken for

granted, as shown in this quote by Bartholomeus Anglais, writing in 1398:

“The cat is often taken for his fair skin and slain and flayed.”

A telling detail from a painting by Herionymous Bosch, titled The

Wayfarer, shows a pedlar carrying his basket of wares on his back, and from the

pack dangles the striped skin of a tabby cat.

|

| Note both the ragged dress of the pedlar, and the tabby cat skin hanging from his pack |

And in Germany, furriers had their own hierarchy with those at the top

working with ermine and other costly furs. But when those lower down the rank

wished to make a cutting insult they would refer to the colleague as a “cat

skinner”, meaning the lowest of the low.

One uncomfortable question is to ask where these cat skins came from.

Undoubtedly many were strays and in poor condition, hence the reputation for

cat skin as a lowly fur. However, at times, domestic cats also fell foul of a

pedlar with an eye to make quick money.

Records exist from 1268 in Paris when the going price was one pence for:

“…the skins of private cats of the fireside or hearth.”

|

| Henry VIII in robes trimmed with ermine. Would you feel differently about the portrait if the fur was cat instead of ermine? |

Of course in medieval times life was hard and it was practical to use

whatever resources were available in order to survive. So using animal skins,

of whatever species, was necessary to stop people freezing to death.

As a cat lover, and a vegetarian for over thirty years, I understand

why medieval people were so practical about the use of animal skins. Before you throw

your hands up in horror, ask yourself are truly

blameless? Why is it OK for one species to provide meat for the table (or

leather for your shoes), but not another?

|

| Cat skins look best on the cat |

.JPG)

.jpg)

.jpg)